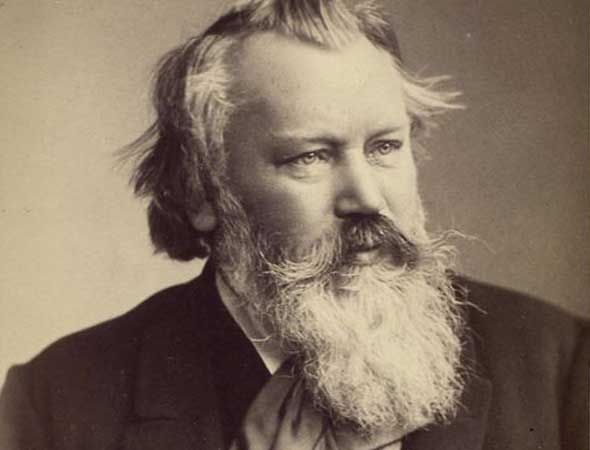

Brahms – Serenade No. 2 in A Major, Op. 16

Performance time: 29 minutes

The relatively low opus numbers of Brahms’s two serenades—this one is Op. 16 and No. 1 is Op. 11—tell us that they are early works. With the benefit of time, we also know that Brahms already had symphonic form on his mind. And some of Brahms’s contemporaries knew this as well—notably his friends and mentors, Robert and Clara Schumann.

Brahms completed his serenades in 1856, two decades before he would complete his first symphony. They were his first serious orchestral works. But Robert Schumann heard “veiled symphonies” in Brahms’s early compositions, even those for the piano. Today we understand that Brahms’s two serenades, composed when he was 23, are pre-symphonic studies in orchestral craft. In fact, we can consider the Serenade No. 2 as Brahms’s first true orchestral work. While the Serenade No. 1 was originally conceived as a nonet for winds and strings—essentially a chamber work—the Serenade No. 2 was scored for orchestra from the outset. For Brahms, this step forward was bold, yet measured: He adopted the loosely structured serenade form, in this case with five movements, to make sure it bore no resemblance to a symphony. Further stressing the dissimilarities, he omitted violins from his instrumentation and added a scherzo before the serenade’s slow movement.

But the biggest factor differentiating Brahms’s serenades from his symphonies could be termed “mood.” When it came to symphonies, Brahms felt that he owed his predecessors and the public something of high purpose and artistic merit. Music-loving Vienna impatiently dubbed his first symphony “Beethoven’s tenth” long before he composed it, and Brahms himself said that “After Haydn, writing a symphony was no longer a joke but a matter of life and death.” We can hear how seriously he took the form in all four of his symphonies; whether in Major or minor mode, there’s not a moment of a Brahms symphony that doesn’t sound “important.”

In Brahms’s serenades, by contrast, relaxation and warmth prevail. The second opens confidently; its melodies meander from A Major to D-flat with seamless Brahmsian craft. The dance movements contrast a rustic scherzo with a refined tempo marked quasi menuetto. At the heart of the serenade is a sumptuously beautiful adagio, hushed and poetic, constructed from a set of variations over a repeated bass line. Clara Schumann singled out this movement for particular praise after her husband died. Though Robert Schumann never lived to hear a performance of this or any of Brahms’s orchestral works, his belief in their potential proved correct.